- Blogs

- Selecting Building Materials for UK Coastal Climates: A Comprehensive Guide

Selecting Building Materials for UK Coastal Climates: A Comprehensive Guide

TLDR

-

Core Challenge: The UK coastal environment combines salt spray, high humidity, wind-driven rain, and erosion risk, which accelerates the degradation of building materials. Successful construction requires a systematic approach to material selection based on resilience.

-

Foundations & Structure: Use reinforced concrete specified to BS 8500, selecting exposure classes (XS1, XS2, XS3) based on proximity to the sea to prevent chloride attack. For structural steel, use hot-dip galvanized coatings to BS EN ISO 1461 or, for maximum protection, marine-grade (A4/316) stainless steel.

-

Walls & Cladding: Choose dense, low-porosity materials like engineering bricks to minimise salt absorption. Use modern silicone or polymer-based render systems for a water-repellent yet breathable finish. For cladding, fibre cement and composite materials offer excellent durability and low maintenance in saline environments.

-

Roofing: All roof coverings must be mechanically fixed according to BS 5534 to resist high wind uplift forces, which are a primary cause of failure in coastal areas. Natural slate and correctly specified metal roofing systems perform very well.

-

Windows & Fixings: Powder-coated aluminium windows offer superior long-term durability and structural strength over uPVC in harsh coastal conditions. All external fixings, including screws, nails, and bolts, must be A4/316 stainless steel to prevent catastrophic corrosion.

-

Design: Follow best practices outlined in British Standards, particularly BS 8104 for assessing rain exposure. Incorporate protective architectural features like deep roof overhangs and ensure excellent internal ventilation to manage moisture and prevent condensation.

1.0 Introduction: Building on the UK Coastline

Constructing a property on the UK's coastline presents a unique set of challenges that demand a specialised approach to design and material specification. The allure of a coastal location is undeniable, but the environment is relentlessly aggressive towards the built form. Longevity, safety, and durability in this setting are not accidental; they are the direct result of informed material selection, meticulous detailing, and a deep understanding of the forces at play.

The pressures on coastal buildings are intensifying. The UK's climate is changing, leading to projections of rising sea levels, more frequent and severe storm events, and increased coastal erosion. These factors mean that building practices and material choices that may have been adequate in previous decades are no longer sufficient for creating resilient, long-lasting structures. The process of selecting materials is therefore not simply about achieving a desired aesthetic but is a critical exercise in risk management.

This guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the environmental factors affecting buildings in UK coastal areas and offers detailed, practical guidance on selecting appropriate materials for every part of the structure. It is intended for those who are building new properties or undertaking significant renovations in coastal locations, providing the technical understanding needed to specify materials that will withstand the demands of this challenging environment for their intended service life. The focus is on a systems-based approach, where the building is considered as a whole, from its foundations buried in the ground to the smallest fixing exposed to the sea air.

2.0 The Demands of the Coastal Environment

The coastal environment's effect on buildings is not due to a single factor but to the combined, synergistic action of multiple aggressive agents. Understanding these forces and how they interact is the first step in designing and specifying a durable structure.

2.1 Salt, Wind, and Water: The Primary Agents of Decay

The three defining elements of the coastal climate—salt, wind, and water—work together to create a uniquely destructive combination. Sea spray, which consists of fine droplets of seawater aerosolised by wind and wave action, can be carried several miles inland, depositing a thin layer of salt on all exposed surfaces.

This salt deposit alone is a problem, but its destructive potential is fully realised when combined with the UK's high levels of rainfall. Wind-driven rain is a particularly significant issue around the UK coastline. Strong, persistent winds can drive raindrops at an angle, or even horizontally, with considerable force. This allows moisture to penetrate building envelopes through tiny cracks, porous materials, and vulnerable junctions in a way that vertical rainfall would not.

When this wind-driven rain saturates a salt-coated surface, the salts dissolve, creating a potent saline solution. This solution is then driven into the fabric of the building, carrying corrosive chlorides deep into porous materials like brick, stone, and concrete. The constant cycle of wetting with salt-laden water and subsequent (often incomplete) drying is the fundamental mechanism of decay that must be resisted.

2.2 Corrosion and Material Degradation: The Chemical Attack

The presence of salt and moisture initiates a series of chemical and physical attacks on building materials. For metals, the primary threat is accelerated corrosion. The dissolved salts in the water create an electrolyte solution, which dramatically speeds up the electrochemical process of rusting in unprotected carbon steel. This leads to a rapid loss of structural integrity in fixings, fasteners, and structural elements. It can also initiate galvanic corrosion, where two different metals in contact with each other in the presence of an electrolyte will cause one to corrode preferentially, often with catastrophic results for the component that sacrifices itself.

For porous masonry materials like brick, render, and concrete, the damage mechanism is more physical but no less destructive. As saline water is absorbed into the material's pores, the salts are left behind when the water evaporates. Over repeated wetting and drying cycles, these salt concentrations build up within the material. When humidity drops or temperature rises, these salts crystallise. This process of crystallisation can cause a massive expansion in volume, generating immense internal pressures within the masonry—enough to physically break down the material from the inside out. This manifests as spalling (flaking of the surface), crumbling, and the general decay of the building fabric. It is the salts, not just the water, that are the primary agent of this irreversible damage.

2.3 The Challenge of High Humidity and Damp

Coastal regions of the UK are characterised by persistently high levels of atmospheric humidity. This constant presence of moisture in the air creates a challenging internal and external environment for buildings. Externally, it means that walls saturated by rain take much longer to dry out, prolonging their contact with moisture and any absorbed salts.

Internally, high external humidity makes it more difficult to manage moisture generated by occupants through cooking, washing, and breathing. When this warm, moist internal air comes into contact with cooler surfaces, such as windows or poorly insulated external walls, the moisture condenses. Persistent condensation leads to damp patches, peeling paint, and the growth of mould, which is detrimental to both the building fabric and the health of its occupants.

This combination of moisture from the outside (penetrating damp from wind-driven rain) and moisture from the inside (condensation) can lead to the saturation of building materials. This reduces the effectiveness of insulation, promotes the decay of timber elements like joists and floorboards, and can cause long-term structural damage. Effective management of both bulk water ingress and internal water vapour is therefore essential.

2.4 Coastal Erosion and Flood Risk: Ground-Level Threats

Beyond the atmospheric threats, buildings on the coast face direct geological risks from erosion and flooding. The UK's coastline is a dynamic system, constantly being reshaped by waves, tides, and storms. Climate change is accelerating these processes, leading to rising sea levels and more frequent storm surges, which increase the rate of erosion and the risk of coastal flooding.

The scale of this threat is significant. In England alone, thousands of properties are currently in areas at risk of coastal erosion, with this number projected to increase substantially over the coming decades. The risk is not uniform and is managed by the Environment Agency through Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs). These plans set out the policy for managing a stretch of coastline, which can range from 'hold the line', where existing defences are maintained or upgraded, to 'managed realignment', where the shoreline is allowed to retreat in a controlled way.

This introduces a crucial consideration for anyone building or buying on the coast. The long-term viability of a property is not just dependent on its physical construction but also on the coastal management policy for its specific location. The design life of the building and the investment in high-durability materials must be weighed against the policy-defined future of the shoreline itself. Material specification in this context becomes a direct response to both natural and political risk.

3.0 Foundations and Structural Frame: The Resilient Core

The longevity of a coastal building is determined by the durability of its primary structure. The foundations and frame must be specified to resist the unseen chemical attacks from salt in the ground and the air, ensuring the building's stability for its entire design life. This is achieved not by guesswork, but by a systematic approach that uses British Standards to quantify the environmental aggression and prescribe a proportionate material response.

3.1 Foundations in Coastal Zones: Specifying Concrete to BS 8500

Standard concrete can be vulnerable in coastal environments. Chlorides from saltwater can penetrate the concrete, eventually reaching the steel reinforcement and initiating corrosion. The resulting rust expands, cracking the concrete from within and compromising the structure's integrity. Additionally, sulphates present in coastal soil and groundwater can attack the cement paste itself, leading to a loss of strength and cohesion.

To counter these threats, concrete for coastal foundations must be specified in accordance with BS 8500: Concrete - Complementary British Standard to BS EN 206. This standard provides a framework for producing durable concrete tailored to specific exposure conditions. For marine and coastal environments, the key designations are the 'XS' exposure classes, which relate to corrosion induced by chlorides from seawater :

-

XS1: Exposed to airborne salt but not in direct contact with sea water. This class is for structures located near the coast but not directly on the shoreline.

-

XS2: Permanently submerged. This applies to parts of a structure that are always below the tidal mark, such as the lower sections of piles or sea walls.

-

XS3: Tidal, splash and spray zones. This is the most aggressive category, covering areas that are subject to repeated cycles of wetting and drying with seawater. This cyclic action actively draws chlorides into the concrete.

For each of these classes, BS 8500 specifies limiting values for factors such as the maximum water-to-cement ratio, the minimum cement content, and the required compressive strength class. A lower water-to-cement ratio results in a denser, less permeable concrete that provides a more effective barrier against chloride ingress. The standard also guides the selection of appropriate cement types. Using cement replacements such as Ground Granulated Blast-furnace Slag (GGBS) can significantly improve the concrete's resistance to both chloride and sulphate attack, making it more durable in marine environments. The correct specification of concrete to BS 8500, combined with ensuring adequate concrete cover over the reinforcement, is the primary defence for substructures in coastal locations.

3.2 Structural Steel: Protection Against Corrosion

All steel used in the structural frame of a coastal building must be robustly protected against corrosion. The constant presence of salt and moisture creates a highly aggressive atmosphere that can rapidly degrade unprotected steel. The level of aggression is formally classified by BS EN ISO 12944-2, which defines corrosivity categories for different environments. Coastal locations in the UK typically fall into the higher categories :

-

C3 (Medium): Coastal areas with low salinity.

-

C4 (High): Coastal areas with moderate salinity.

-

C5-M (Very High - Marine): Coastal and offshore areas with high salinity.

-

CX (Extreme): Offshore areas and exposed headlands with very high salinity.

The choice of protective system for structural steel must be appropriate for the corrosivity category of the specific site. The two principal methods for providing long-term protection are hot-dip galvanizing and the use of stainless steel.

Hot-Dip Galvanizing is a process where the fabricated steel component is submerged in a bath of molten zinc. This creates a tough, metallurgically bonded coating that protects the steel in two ways. Firstly, it provides a physical barrier, sealing the steel from the atmosphere. Secondly, it offers sacrificial protection; if the coating is scratched or damaged, the surrounding zinc will corrode in preference to the exposed steel, preventing rust from creeping under the coating. For this protection to be effective in coastal zones, the zinc coating must be of sufficient thickness, as specified in BS EN ISO 1461. For C3 environments and above, a minimum average coating thickness of 85µm is typically required to provide a design life of several decades.

Stainless Steel offers the highest level of corrosion resistance and should be considered for the most critical or exposed structural elements. However, it is essential to specify the correct grade. While A2 (or 304) grade stainless steel is suitable for general outdoor applications, it is susceptible to pitting and crevice corrosion in chloride-rich environments. For coastal construction, marine-grade A4 (or 316) stainless steel is mandatory. This grade contains molybdenum, which provides significantly enhanced resistance to corrosion from chlorides and is the standard for marine and coastal applications.

4.0 The Building Envelope: Walls, Render, and Cladding

The building envelope is the primary barrier against the elements. Its design and material composition are critical for preventing water penetration, managing moisture, and resisting the degrading effects of salt and wind.

4.1 Masonry Selection: The Importance of Low Porosity

The choice of brick or block for external walls in a coastal location should be guided by the principle of minimising water absorption. Porous materials can act like a sponge, drawing in wind-driven, salt-laden rain and holding it within the wall, leading to internal damp and salt crystallisation damage.

While standard clay bricks can be used, denser, less porous options provide a more robust solution. Engineering bricks are an excellent choice for the outer leaf of a cavity wall in exposed locations. They are manufactured to have high compressive strength and, crucially, very low water absorption rates. This inherent density makes them highly resistant to saturation and to the freeze-thaw cycles that are made more damaging by the presence of salts.

Where a rendered finish is planned, dense concrete blocks provide a stable and durable substrate. Regardless of the material, the quality of workmanship is paramount. Mortar joints must be fully filled, and the use of a mortar admixture such as a styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) polymer can help to increase the density and reduce the permeability of the mortar itself, further resisting moisture penetration.

4.2 Render Systems: A Protective Overcoat

A well-specified render system provides a seamless, weatherproof coating that protects the masonry substrate. Traditional sand and cement renders can perform adequately but are rigid and prone to cracking over time, creating pathways for water to enter the wall. In the demanding coastal environment, modern polymer-modified systems offer superior performance.

Silicone-based renders are particularly well-suited to coastal properties. These advanced systems are highly water-repellent (hydrophobic), causing rain to bead up and run off the surface rather than being absorbed. At the same time, they are vapour-permeable, or 'breathable', which means that any moisture that does get into the wall structure can escape as vapour. This combination of preventing liquid water from getting in while allowing water vapour to get out is ideal for managing moisture in damp coastal climates. Many silicone renders also have self-cleaning properties that resist the growth of algae and lichen, helping to maintain the building's appearance.

Polymer and acrylic renders also offer enhanced flexibility compared to traditional mixes, making them more resistant to cracking caused by thermal movement of the building. When specifying any render system in a coastal location, it is a critical detail to use only PVC or stainless steel render beads for all corners and edges. Standard galvanised steel beads will corrode rapidly when exposed to salt, leading to rust staining and failure of the render at its most vulnerable points.

4.3 Cladding Solutions: Durability and Low Maintenance

Cladding offers another robust approach to creating a weatherproof building envelope, often in the form of a rainscreen system where an outer decorative layer protects a ventilated and insulated cavity behind. The choice of cladding material for a coastal home should prioritise resistance to salt, moisture, UV radiation, and wind.

Fibre cement is a highly durable, low-maintenance option. It is a composite material made from cement, sand, and cellulose fibres, which is immune to rot, resistant to salt spray, and does not warp or crack when exposed to moisture. It is available in a wide range of colours and finishes, including boards that mimic the appearance of timber.

Composite cladding, often made from a mixture of recycled wood fibres and plastic, is another excellent low-maintenance choice. It combines the aesthetic appeal of wood with the durability of plastic, making it resistant to rot, insects, and moisture degradation from saltwater.

Metal cladding, such as aluminium or specially coated steel, offers a modern aesthetic and is very durable in high-wind locations. Aluminium is naturally resistant to corrosion. For steel systems, a marine-grade coating is essential to prevent rusting.

Treated timber can be used to create a natural, warm aesthetic that blends well with coastal landscapes. Species with a high natural resistance to decay, such as Western Red Cedar or Siberian Larch, are preferred. Alternatively, timber can be thermally modified (e.g., Thermowood) to greatly increase its stability and resistance to rot. All timber cladding will require some maintenance and will weather over time to a silver-grey patina unless treated with a UV-protective finish.

The following table provides a comparative overview of common cladding materials for coastal applications.

Material Type |

Salt/Corrosion Resistance |

Maintenance Requirement |

Durability/Lifespan |

Indicative Cost |

Aesthetic Notes |

| Fibre Cement | Excellent | Very Low | Very High (40+ years) | Medium | Can mimic timber or provide smooth panel finish. Wide colour range. |

| Composite (WPC) | Excellent | Very Low | High (25+ years) | Medium to High | Consistent appearance, mimics timber. Can look less natural than real wood. |

| Marine-Grade Aluminium | Excellent | Very Low | Very High (40+ years) | High | Modern, sleek appearance. Wide range of powder-coated colours. |

| Treated Timber (e.g., Cedar) | Good (natural oils) | Medium (periodic cleaning/re-oiling to maintain colour) | Good (20-40+ years depending on species/treatment) | Medium to High | Natural, warm aesthetic. Weathers to a silver-grey if left untreated. |

| uPVC | Excellent | Very Low | Medium (20+ years) | Low | Can look like plastic. Colour may fade over time with UV exposure. |

5.0 Roofing Systems for High Wind and Rain Exposure

The roof is a building's most exposed element, bearing the full force of wind and rain. In a coastal setting, the design philosophy for roofing must shift from simply providing an 'umbrella' to engineering a structural system capable of resisting significant wind uplift forces. Failure to do so is a common cause of catastrophic damage during storms.

5.1 Roof Coverings: Performance in Harsh Conditions

While the fixing of the roof is the most critical aspect, the choice of covering material is also important for long-term durability.

Natural slate is an outstanding performer in marine environments. High-quality slate, such as that from Welsh quarries, is extremely dense and has virtually zero water absorption. This makes it impermeable to water and highly resistant to the damaging effects of salt spray and freeze-thaw cycles. It is also unaffected by UV light, retaining its colour, and has a service life that can be measured in centuries.

Clay and concrete tiles are also widely used, but it is important to select high-quality products with low porosity to minimise water absorption. For any tiled roof, the security of the roof depends entirely on the fixing specification.

Metal roofing, particularly standing seam systems, offers an excellent combination of durability and wind resistance. Materials such as marine-grade coated steel, aluminium, or copper are lightweight yet strong, and when installed as a fully supported system, they create a continuous weatherproof layer with very few joints for wind to exploit. They are highly resistant to corrosion when specified with the correct marine-grade finishes.

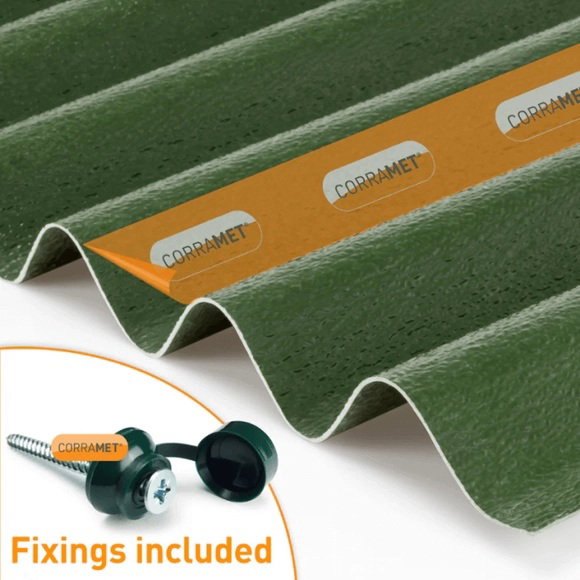

5.2 Underlays, Fixings, and BS 5534

The security of a pitched roof in the UK is governed by BS 5534: Code of practice for slating and tiling. Adherence to this standard is essential for any coastal property and is a requirement for warranty providers and building control. The standard was significantly updated in response to the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, with a primary focus on improving the roof's resistance to wind uplift.

The key principles of BS 5534 for high-wind locations are:

-

Mechanical Fixing: The standard mandates that every single tile or slate must be mechanically fixed. For single-lap tiles, this means each tile must be secured with at least one nail and/or a clip. All tiles on the perimeter of the roof (verges, eaves, ridges, hips) must be fixed at least twice.

-

Prohibition of Mortar-Only Bedding: Mortar can no longer be relied upon as the sole method for securing ridge and hip tiles. While it can be used for bedding, these components must also be mechanically fixed in place, typically as part of a dry-fix system.

-

Wind Uplift Calculations: BS 5534 provides a detailed calculation method to determine the wind uplift forces that a specific roof will be subjected to. This calculation takes into account the building's geographical location on the UK wind speed map, its altitude, the local topography (e.g., on a hill or in a valley), and any shelter from surrounding buildings or trees. The result of this calculation determines the precise fixing specification required—for example, the size and type of nails, and whether single or double nailing, or additional clips, are needed.

-

Roofing Underlay: The underlay (or membrane) beneath the tiles and battens plays a crucial role in secondary weather protection and must also be sufficiently resistant to wind loads. The standard specifies requirements for securing underlay laps to prevent them from being lifted by wind blowing into the roof space.

The integrity of this entire system depends on the durability of its smallest components. All nails, clips, and other fixings used on the roof must be made from A4 (316) grade stainless steel or another suitably corrosion-resistant material to prevent failure due to rust.

6.0 Windows, Doors, and Essential Fixings

Openings in the building envelope are potential weak points that must be carefully specified to resist wind-driven rain and corrosion. The choice of window frame material and the specification of every external fastener are critical details that have a major impact on the long-term performance and maintenance of a coastal property.

6.1 Window Frame Materials: uPVC vs. Powder-Coated Aluminium

The two most common choices for window frames in the UK are unplasticised polyvinyl chloride (uPVC) and aluminium. Both can perform in a coastal environment, but they offer different balances of performance, durability, and cost.

uPVC windows are a cost-effective option and have good inherent resistance to moisture and salt. The material itself does not corrode, rot, or rust, making it very low-maintenance. High-quality uPVC frames offer excellent thermal performance due to their multi-chambered profiles, which trap air and reduce heat transfer. They can provide a service life of around 20-30 years in a coastal setting if properly maintained.

Powder-coated aluminium windows are generally considered the more durable, long-term solution for exposed coastal locations. Aluminium is an inherently stronger material than uPVC, which allows for much slimmer frames. This maximises the glass area, improving views and allowing more natural light into the building. While raw aluminium can corrode, modern window frames are protected by a factory-applied powder coating. When a marine-grade powder coating is specified, it provides a tough, durable barrier that is highly resistant to salt spray and corrosion. Aluminium windows have a longer potential lifespan, often cited as 45 years or more, but they have a higher initial cost than uPVC.

The choice between the two often comes down to balancing budget against long-term durability and aesthetic preference. While good quality uPVC is a viable and popular choice, for the most exposed sites, the superior strength and proven longevity of marine-grade powder-coated aluminium make it the premium option.

The following table compares the key features of uPVC and powder-coated aluminium windows in a coastal context.

Feature |

uPVC |

Powder-Coated Aluminium |

| Salt Corrosion Resistance | Excellent (material is inherently non-corrosive) | Excellent (with marine-grade powder coating) |

| Durability & Lifespan | Good (20-30 years) | Excellent (45+ years) |

| Strength (Frame Slimness) | Lower strength requires thicker, bulkier frames. | High strength allows for very slim, minimalist frames. |

| Maintenance | Very Low (requires occasional cleaning) | Low (requires occasional cleaning; coating should be checked periodically) |

| Thermal Performance | Excellent (multi-chambered profiles provide good insulation) | Very Good (modern frames include thermal breaks to rival uPVC) |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

6.2 Glazing and Weather Tightness

The performance of a window or door unit is not just about the frame material. The entire assembled product must be able to resist the forces of wind and rain. BS 6375-1 is the British Standard that classifies the weather performance of windows and doors. It tests and rates them for:

-

Air Permeability: How well they prevent draughts.

-

Water Tightness: Their ability to resist leaking under wind-driven rain.

-

Wind Resistance: Their structural strength to resist flexing or damage under high wind loads.

When selecting windows and doors for a coastal property, it is essential to choose products with a performance classification appropriate for the site's exposure level. A high-quality installation, using appropriate sealants and gaskets to create a continuous weatherproof seal between the frame and the building structure, is just as important as the product itself.

6.3 Fixings and Fasteners: The Critical Detail

A recurring and absolutely critical theme in coastal construction is the specification of all external metal components. A durable, expensive cladding panel or window frame can be completely undermined if it is fixed to the building with a fastener that corrodes and fails. Rusting fixings not only cause unsightly staining but also lead to a loss of structural integrity, which can be dangerous in high winds.

For this reason, a non-negotiable rule for coastal building is that all external fixings and fasteners must be made from marine-grade A4 (316) stainless steel. This includes every screw, nail, bolt, bracket, and clip used on the exterior of the building, from roofing nails and cladding screws to the fixings for satellite dishes and railings. Using cheaper A2 grade stainless steel or galvanised steel fixings is a false economy that will inevitably lead to premature failure and costly repairs. The superior chloride resistance of A4 (316) stainless steel is essential for ensuring the security and longevity of the entire building envelope.

7.0 Key UK Standards and Design Best Practices

Successful coastal construction relies on a framework of established standards and design principles. These provide a systematic method for assessing environmental risks and specifying appropriate solutions, moving beyond anecdotal evidence to a robust, engineering-led approach.

7.1 An Overview of Essential British Standards

Throughout this guide, several key British and European standards have been referenced. They form the technical backbone of durable coastal design and construction in the UK. The following table provides a summary of the most important standards and their relevance.

Standard Number |

Title |

Relevance to Coastal Construction |

| BS 8500 | Concrete - Complementary British Standard to BS EN 206 | Specifies durable concrete mixes for different exposure conditions, including the 'XS' classes for marine environments, to resist chloride and sulphate attack. |

| BS EN ISO 1461 | Hot dip galvanized coatings on fabricated iron and steel articles | Defines the requirements for hot-dip galvanized coatings, including minimum coating thickness, which is critical for protecting structural steel from corrosion. |

| BS EN ISO 12944-2 | Corrosion protection of steel structures by protective paint systems - Part 2: Classification of environments | Classifies the corrosivity of atmospheric environments (C1 to CX), allowing for the correct specification of protective coatings for steel in coastal (C4, C5-M, CX) zones. |

| BS 5534 | Code of practice for slating and tiling | The primary standard for pitched roofing in the UK. It mandates mechanical fixing of all roof coverings and provides methods for calculating wind loads to ensure roof security. |

| BS 8104 | Code of practice for assessing exposure of walls to wind-driven rain | Provides a method for calculating a site's specific exposure to wind-driven rain, which informs the design of walls and the selection of materials to prevent water penetration. |

| BS 6375-1 | Performance of windows and doors - Part 1: Classification for weathertightness | Classifies windows and doors based on their resistance to air, wind, and water penetration, ensuring they are suitable for the exposure level of the site. |

7.2 Design for Durability: Managing Water

Beyond material choice, certain architectural design features can significantly improve a building's ability to manage water and resist the effects of wind-driven rain. The fundamental principle is to shed water from the building's face as effectively as possible and to protect vulnerable junctions. Best practices include:

-

Deep Roof Overhangs: Generous eaves and verges provide an 'overcoat' for the walls below, offering significant protection from rainfall and reducing the amount of water that runs down the facade.

-

Projecting Sills: Well-designed sills beneath windows and other openings should have a clear projection and a drip groove on the underside. This throws water clear of the wall below, preventing it from concentrating and running down the face of the building.

-

Avoiding Flush Detailing: Architectural details where surfaces meet flush, without an overhang or protective flashing, should be avoided in exposed locations. These junctions are highly vulnerable to water penetration driven by wind pressure.

The starting point for these design decisions should be a formal assessment of the site's exposure using the methodology set out in BS 8104. This standard allows a designer to calculate a 'spell index' for the site, which quantifies the likely severity of wind-driven rain, taking into account national weather data along with local factors like topography and shelter. This provides an objective basis for determining how robust the wall construction and detailing needs to be.

7.3 Ventilation and Moisture Control

A final, critical element of durable coastal design is the management of internal moisture. A 'build tight, ventilate right' strategy is essential. While the building envelope should be made as airtight as possible to prevent draughts and uncontrolled heat loss, a controlled ventilation strategy must be put in place to remove the water vapour generated by occupants and prevent condensation.

Effective strategies include:

-

Local Mechanical Extraction: High-performance extractor fans in 'wet' rooms like kitchens and bathrooms are essential for removing moisture at its source.

-

Background Ventilation: Properly sized trickle ventilators in windows and air bricks should be incorporated to ensure a constant supply of fresh air. These ventilation paths must be kept clear and unobstructed.

-

Whole-House Ventilation: In new, highly airtight homes, a Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery (MVHR) system may be the most effective solution. These systems provide a continuous supply of fresh, filtered air while extracting stale, moist air, and they recover a significant portion of the heat from the outgoing air, improving energy efficiency.

By combining a weatherproof external envelope with a well-ventilated interior, a building can effectively manage moisture from both inside and out, ensuring a healthy and durable internal environment.

8.0 Conclusion: Principles for Durable Coastal Construction

Building successfully on the UK coastline is a demanding but achievable goal. It requires a departure from standard construction practices and an embrace of a proactive strategy founded on resilience. The environmental forces of salt, wind, and water are relentless, and their effects are being amplified by a changing climate. A durable coastal building is therefore one where this reality has been acknowledged and addressed at every stage of its design and construction.

The core principles for success can be synthesised from the detailed guidance. First is the adoption of a systems-based approach, recognising that materials do not perform in isolation. A high-performance render is only effective on a suitable substrate with non-corroding beads; a durable roof tile is only secure if its fixings are correctly specified to resist wind uplift. The entire assembly, from the structural frame to the smallest fastener, must work in concert.

Second is the critical importance of an evidence-based specification process, guided by British Standards. These standards provide the essential tools to diagnose the specific environmental challenges of a site—from concrete exposure classes under BS 8500 to wind-driven rain severity under BS 8104—and prescribe a proven, engineered solution. This systematic approach replaces assumption with calculation, ensuring that the specified materials are proportionate to the risks they face.

Finally, the design must be rooted in the fundamental principles of water and moisture management. This involves both shedding bulk water from the exterior through intelligent architectural detailing and controlling water vapour on the interior through effective ventilation. By designing a building that can stay dry, inside and out, its material components are protected from the primary mechanisms of decay. By adhering to these principles, it is possible to create buildings that not only survive but thrive on the UK's beautiful and challenging coastline.

9.0 Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this article is provided for general guidance and informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute legal, architectural, engineering, or other professional advice, and it should not be relied upon as such.

The selection and specification of building materials and construction methods should only be undertaken after seeking advice from appropriately qualified and insured professionals, such as architects, structural engineers, and chartered surveyors, who can assess the specific circumstances of your project. The application of building regulations and standards will vary depending on the unique factors of each site and project, and such regulations and standards are subject to change.

While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy and currency of the information provided, no guarantees, conditions, or warranties are made as to its accuracy or completeness. We disclaim all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the materials contained in this article. We shall not be liable for any errors or omissions, or for any loss or damage of any kind arising from the use of this information. You should neither act, nor refrain from acting, on the basis of any information contained herein without first seeking professional advice.

Samuel Hitch

Managing Director

Buy Insulation Online.

Leave A Reply

Your feedback is greatly appreciated, please comment on our content below. Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *